Remember when the internet used to be fun? Whitney Phillips does. The digital anthropologist was recently looking through a huge set of images from the late 2000s that had been posted to Reddit. The first comment described the era as “a more simple time,” and sure enough, the pictures were weird, silly, and creative. Talking cows. Cats playing video games. A bear on a golf course. A guy Photoshopped to have mouths for eyes.

Then she noticed something else. Something disturbing. The thread began, she wrote recently, “with a lighthearted meme about Hitler.” After that was “dehumanizing mockery of a child with disabilities. And more sneering mockery of an old man hooked up to an oxygen tank. And date rape. And violence against animals. And fat shaming. And homophobia. And racism. And pedophilia. And how hilarious 9/11 was.”

If you’ve spent any time online, you will have imbibed both the aesthetic and, perhaps, the ethics of “meme culture” or “internet culture.” This is the mashed-up jumble of images, jargon, and folk art that gushed out of sites such as 4chan, Reddit, and Tumblr from the late 2000s. The look was lo-fi and absurdist, and the tone was eye-rolling, cynical, self-aware. Blocky white letter captions on pictures of exaggerated facial expressions. “HALP,” “OHRLY,” “KTHXBYE.” Adorable cat GIFs.

In the 2000s and early 2010s, Phillips was one of a group of academics, activists, and intellectuals who studied memes, and promoted the idea of the web as a space of unfettered, anarchic creation. The revolution would be user-generated. (The founders of social networks—primarily young, carefree, middle-class white Americans—agreed.) Okay, the argument went, this outpouring of creativity had its darker elements, but that was part of its countercultural charm. The casual sadism of trolling was just “lulz,” which shouldn’t be taken seriously. Sexism, racism, and other hatreds were being invoked for nothing more than shock value. It was ironic, duh.

In 2009, she attended a live show called Meme Factory, which aimed to explain this new language of the internet. Three young men sat in front of microphones, talking deliberately fast, occasionally projecting pictures onto the screen behind them. There were “fails”; there were “owns”; the viewers didn’t have to think much about the people who were the butt of the joke. The first Meme Factory show began with a disclaimer about its offensive content, delivered in front of a picture of a white cat captioned with what was a popular phrase at the time: Internet. Serious Business. Phillips remembers laughing until she cried at a repeat performance the next year. There was an assumption that everyone in the room “got it,” that they understood who was being satirized—the racists and the homophobes—and that everything was just for lulz.

But the blizzard of memes didn’t allow any time to distinguish between the cute and the offensive, the innocuous and the hateful. One section, Phillips recalled, showed “several internet-infamous young white women who had inspired widespread mockery online.” Such women, the three men explained, were referred to as “camwhores.” When the photograph of one flashed on-screen, the crowd booed. A man in the audience shouted: “Kill her!”

Phillips, an assistant communications professor at Syracuse University, now thinks she got it wrong. All that ironic racism doesn’t feel so ironic anymore. “I don’t even know exactly when it totally shifted,” she told me, from her yellow-painted living room in Syracuse, New York, her hands anxiously fluttering around her face as we spoke over Zoom. “What seemed to be fun and funny ended up functioning as a Trojan horse for white-supremacist, violent ideologies to shuffle through the gates and not be recognized.”

The 2010s were the decade when internet culture ate real life; when the boundary between “IRL” and “on the internet” dissolved. By the time the decade ended, a certain kind of liberal was forced to accept that we had been far too complacent about how dark politics could get, and how the ironically awful parts of the internet helped that to happen. Many others have walked down the same path of recognition as Phillips. What was once dismissed as “trolling” is now recognized as harassment and abuse; where flat earthers and 9/11 truthers once seemed laughable, today’s conspiracy theorists commit acts of violence.

Watching the Meme Factory video again a decade later, what once seemed like consequence-free, playful transgression now looked toxic. The shout of “Kill her!,” which anticipated the sexism of Gamergate, was particularly haunting. “Too many of us just didn’t see it, or if we did, we just didn’t think it was real misogyny,” Phillips said. “The mystique of lulz, the fun of lulz, was too ethically paralyzing.”

Actual-bigotry-camouflaged-as-ironic-bigotry seems like a new phenomenon, perhaps even a quintessentially 21st-century one, dependent on a mashup of consumerism and pop culture and being Very Online. Modern extremism often comes with elements of silliness and ridiculousness. Look at the “boogaloo” movement, a militia named after the obscure ’80s film Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, whose followers expect a second civil war in the United States. They are preparing for that eventuality by attending anti-lockdown protests and gun-rights rallies in jaunty Hawaiian shirts under stab vests, carrying assault weapons. Look at the extraordinary set of beliefs held by QAnon conspiracists, about sex-trafficking satanists operating in family restaurants. Look at Pepe the cartoon frog, a symbol that white supremacists co-opted from its creator, who once shamefacedly explained that it was so named because it sounded like pee-pee. To misquote The Big Lebowski, say what you like about the tenets of national socialism, but at least the Nazis took themselves seriously.

But that’s not right—bigotry and absurdity have long been intertwined. The Ku Klux Klan adopted a deliberately ridiculous name, and Klansmen claimed that they came from the moon, the historian Elaine Frantz Parsons writes in Ku-Klux. They endeavored “to portray victims’ entirely rational fear of their physical violence as though it were superstition or gullibility. The victim, tellingly, failed to ‘get the joke,’ allowing himself or herself to be frightened by ‘ghosts’ or ‘devils.’” The pattern repeated itself in the 20th century. “The Nazis were dedicated trolls who weaponized their insincerity to take advantage of liberal societies ill-equipped to confront them,” as my colleague Adam Serwer put it.

That comparison is also made by Robert Evans, a journalist with the investigative website Bellingcat. When I reached him late one night after he’d spent the day covering protests in Portland, Oregon, his tone was apocalyptic and his delivery staccato. He told me the story of Hans Litten, a Jewish lawyer who prosecuted Nazi paramilitaries for an attack on a dance hall in 1931, and therefore had the chance to cross-examine Hitler. At a time when foreign correspondents and diplomats were still joking about the future dictator’s clownishness, vulgarity, and overheated rhetorical style—and arguing that his overt anti-Semitism, disregard for the law, and advocacy of violence were just tactics to whip up his base—Litten took him seriously. He questioned Hitler carefully, exposing his double-faced strategy: street violence to galvanize an army of thugs, overlaid with a veneer of plausible gentility to attract middle-class voters.

Litten embarrassed Hitler, but did not win the case. And as soon as Hitler came to power in 1933, the lawyer was arrested. After five years of torture and hard labor, Litten killed himself in Dachau.

Evans saw parallels between the world’s refusal to heed Litten’s warnings and his own quest to report on violent militias in the United States. He was worried that far-right extremists—some of whom he had seen in Portland, when the Trump administration sent armed officers from a ragbag of federal agencies to quell protests in the city—were hiding in plain sight, exploiting the plausible deniability created by irony. Take the “OK” hand gesture. To some self-identified trolls, it has been a good joke to hoax the mainstream media into reporting that something so innocuous is a white-supremacist symbol. (Do you find that funny?) But then a theme-park employee in Orlando, Florida, made the sign while posing for a photograph with a 6-year-old Black girl. (Still funny?) And then a mass shooter made the sign in the dock after killing 49 people in New Zealand with a rifle inscribed with the number 14, having left behind a manifesto about “the great replacement” of the white race. (Still funny?)

Extremists “rile people up by making these symbols and then denying that there’s anything racist about them,” Evans told me. “The goal is to make people who are actually watching out for this shit look like they’re crazy to folks who haven’t been paying enough attention to this.”

In other words, don’t be distracted by the silly cartoon frog that extremists have appropriated; worry about the existence of so many extremists posting Pepe memes. Don’t look at the gaudy aloha shirts the militiamen are wearing; look at the serious weapons they’re carrying. Don’t focus on the fact that QAnon asks supporters to believe that Donald Trump is our only defense against cannibalistic satanists; focus on how they will react if he loses in November.

There is another way to describe him: a neo-Nazi. Since leaving prison, Auernheimer has served as the webmaster of The Daily Stormer, an explicitly Nazi website. He has a swastika tattoo on his chest. In writings scattered across the internet, he gives out advice on how to radicalize left-wingers and liberals, boasting that “9 messages is all it takes to get a likely Bernie Sanders supporter asking where they can sign up for the race war.”

Not that you would have guessed this from the contemporary accounts of Auernheimer’s sentencing. Writing for Medium in 2014, his friend Quinn Norton, another champion of internet culture, described him as “far from innocent,” “no hero,” and a “witch for this century.” The words racist and Nazi do not appear, although she concedes that “his skin is pale, and he often talks like a white supremacist, at least around people that are likely to react to such things.” It is a telling construction, framing Auernheimer’s overt racism as a posture—a windup to those not sophisticated enough to understand the deliberately offensive register of trolling, the kind of normies who would take offense at the name of his organization, GNAA, where the second letter stands for the N-word.

I put this to Norton: Her friend didn’t “talk like a white supremacist”; he was a white supremacist. The normies who reacted with horror were correct, and the geeks who brushed it off were wrong. She was hard to pin down, veering instead into a story about the siege of Münster, Germany, and its relationship to the rise of pamphleteering in medieval Europe. “The internet didn’t make any of these problems,” she replied over WhatsApp. “It just intensifies things … When I was working with [the hacker group] Anonymous in 2011, everything was offensive, but nothing was personal, and that was the point. The white supremacists can hide in that, but it’s not their actual thing.”

Meme culture originally came from the 4chan bulletin board, as did Anonymous. The atmosphere of the site is hard to describe: a frenetic churn of slurs, porn, in-jokes, and random conversations. Everyone is anonymous, which has strange results. It’s incredibly hard for outsiders to understand what’s going on, and every user is assumed to be a young American white man. (Two common phrases sum up the attitude: “There are no girls on the internet” and “Tits or GTFO,” as in, show your breasts or get out.) The resulting culture had little patience for progressive politics, whose supporters were assumed to have a victim mentality, and, worse, no sense of humor. Too many women and minorities were hung up on “identity politics” whereas, in this formulation, being a white man was not an identity but the default state of humanity. Not taking offense at sexism proved that you were one of the guys.

Those who championed Auernheimer as a “trickster” before his sentencing follow a narrative that prison changed him. This argument is heavily resisted by the game developer Kathy Sierra, who was a victim of one of his harassment campaigns five years before the AT&T case—he posted her address and Social Security details online. She received death threats. The way she sees it, being blasé about Auernheimer’s sexist harassment was a gateway drug to being blasé about his other opinions. “It was only when his racism became too blatant to ignore that his former champions began to back away,” Sierra told me over email. “The horrific things he did to women had very little impact.”

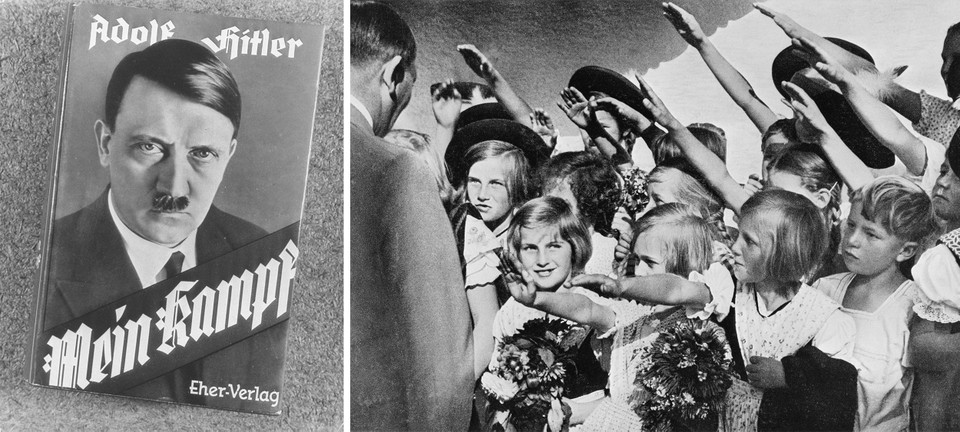

The irony, shocking humor, and plausible deniability that Auernheimer learned to cultivate in troll circles is now being put to use in white-supremacist recruitment. In 2017, HuffPost obtained the style guide for The Daily Stormer. “Generally, when using racial slurs,” the guide advises, “it should come across as half-joking—like a racist joke everyone laughs at because it’s true. This follows the generally light tone of the site. It should not come across as genuinely raging vitriol. That is a turnoff to the overwhelming majority of people.” The site should draw people in through “naughty humor” before they are “slowly awakened to reality,” the guide adds, before recommending that would-be contributors read chapter six of Mein Kampf.

It was that book—Hitler’s political memoir—that made Evans realize just how serious some of the users of 4chan’s politics board, /pol/, were about their beliefs. In the middle of “ironic Holocaust meme threads,” he found long arguments about “different translations of Mein Kampf, and which were truest to the spirit of what Hitler was trying to get across. That’s not fucking around, you know?”

By the way, present at the very first Meme Factory performance, watching the crowd laugh at a satirical deconstruction of white supremacy? Andrew Auernheimer.

When did the fun turn sour? When I spoke with Phillips’s regular collaborator Ryan Milner, he recalled submitting a journal article on memes in 2013. One of the reviewers criticized him for casually including images of people who had not consented to being the butt of a thousand viral jokes. “It was basically calling me flippant,” he told me over the phone. “I went, Man, that reviewer is right.”

Milner realized that he had viewed the memes with “fetishized sight,” a term derived from Marx, which describes how we fixate on the object in front of us and ignore how it was made. It’s the same process that allows us to look at a dirt-cheap item of clothing and refuse to consider how it could possibly be produced for so little. In 2010, when the “Bed Intruder” meme racked up 147 million views on YouTube, people all over the internet laughed at the funny Auto-Tuned remix of a man being interviewed by a news reporter: “Hide your kids, hide your wife … They’re raping everybody out here.” Except the man in question was talking about the attempted rape of his sister. How did he feel about the viral mockery? How did she feel? Jokes about rape were a staple of meme culture, based around the idea that it was shocking to joke about the worst thing that could happen to you. Except, of course, for an American man outside the prison system, it wasn’t all that likely to happen to you.

It happened to Phillips, though. She was raped in 2010, she told me, “four feet from the spot where I sat every night and collected all of my data to write my dissertation, which turned into my book.” (She did not file a police report because she was not ready to go public, and because she feared that the trolls she was studying would find out.) Her abuser used the language of lulz to justify his behavior: Friends would see the bruises on her arms, and he would shrug it off as horseplay. When I asked Phillips if she was okay with me writing about her rape, she said yes. She wanted to acknowledge how the trauma had affected her life and her work. “I cannot tell you how much I regret the fact that it took me experiencing violence to be able to understand what violence was for others,” she added.

Mike Rugnetta, one of the writers behind Meme Factory, told me he, too, now regrets increasing the notoriety of “hateful communities on places like 4chan and Reddit while proselytizing for the more positive aspects of ‘user-generated content.’” The way the show “brushed off” offensive content, he added, “must—must—have hurt some portion of our audience in the process. That thought alone is enough to make my stomach churn.”

For many others, the watershed came later, with Trump’s election. Whatever else he was, the aspiring president was funny. He made shock-humor remarks—tame by the standards of 4chan, but jaw-dropping by the staid standards of mainstream politics—on Rosie O’Donnell’s weight, Ted Cruz’s wife’s looks, John McCain’s capture in Vietnam. He often behaved, at debates with Hillary Clinton, like a heckler. Even now, he regularly draws laughs from unsympathetic audiences: Asked recently by a White House reporter about whether he was really saving the world from “cannibal pedophiles,” he deadpanned: “Is that supposed to be a bad thing?”

By contrast, social-justice activists have often looked like buzzkills. The rise of social media has exacerbated fears that “you can’t say that,” and a majority of Americans (including racial minorities) believe “political correctness has gone too far.” In this climate, offensive jokes are re-spun as “punching up”: The target isn’t oppressed minorities, but a tiny group of liberal elites who want the world to talk like a stern email from the HR department.

In 2016, reporters struggled with these invisible incentives. Who wants to look out of touch with “real America” or like a joyless nag? Millennial reporters on the internet-culture beat gleefully shared the “dankest” pro-Trump memes, even as their colleagues on the politics and opinion desks snickered over Trump’s rambling speeches, oddly capitalized tweets, and contradictory statements. The tone was eye-rolling, cynical, self-aware. We get the joke.

As the campaign wore on, an argument broke out about whether Trump, like the trolls, should be taken “seriously” or “literally,” and whether his racism and indulgence of violence at campaign rallies were truly sinister or “just” the behavior of a political entertainer playing to his base. But so what if he was calling Mexicans rapists only for the lulz, as a windup, to shock the libs? The effect—the weakening of taboos and democratic norms—was real.

Trump’s victory prompted a bout of soul-searching about what, exactly, internet hipsters had been prepared to tolerate, as well as the knowing, complacent tone the media had adopted when covering “ironic” hate speech. Former champions of internet culture felt the chill of a new consensus. Norton’s immersion in trolling culture derailed her career. In 2018, she was hired, and then fired, by The New York Times within a span of six hours. The newspaper said it was unaware of tweets such as one from 2013 in which Norton described an antagonist as a “shit eating hypersensitive little crybaby fag.” She said that to be accepted in hacker circles, she had used “taboo” and “in-group” language—and that as a pacifist, she was unable to reject Auernheimer’s friendship, even though she abhorred his views.

The mood had changed. After a six-year break, the Meme Factory returned in 2017 with a one-off show addressing the role of memes in fueling racism and the “alt-right.” It was called “The Internet Was a Mistake.”

Last year, the FBI warned against “fringe conspiracy theories” as a domestic terror threat. One of these is QAnon, which has retooled the most powerful anti-Semitic tract ever published—The Protocols of the Elders of Zion—for the internet age. It also revives old slurs, but instead of openly accusing Jews of drinking the blood of gentile children, various euphemisms are employed: “Coastal elites,” “Hollywood,” and “George Soros” are now said to be harvesting a chemical called adrenochrome to prolong their life spans. In July, Twitter imposed restrictions on 150,000 accounts linked to QAnon. A month later, Facebook deleted a QAnon group with 200,000 members as part of a wider crackdown. TikTok has blocked QAnon-related hashtags from search results.

Still, because much of the discussion is happening in closed groups, regular internet users can be happily oblivious to its scale. There have been several acts of violence linked to QAnon already, and some supporters talk in apocalyptic terms about the election. One woman interviewed by Time recently said that she was so worried about child trafficking by “the cabal” that if Joe Biden wins the presidential election, “I would probably take my children and sit in the garage and turn my car on, and it would be over.” Some might turn their fear outwards, onto the world. Evans of Bellingcat estimates that there are “a couple of million” Americans who would support fascism. Other experts demur—Joseph Uscinski, who researches QAnon, believes that less than 5 percent of Americans support violence against the government. “Who knows the percentage of who’s actually a Nazi?” said Phillips, referring to sites such as 4chan and its successors 8chan and 8kun. “But what you can say is that the people who spend time in those spaces are people who certainly have the stomach for it.”

It’s not hard to find experts who think that America’s security services ignored the threat of far-right extremists in the post-9/11 years because they were so focused on Islamist terror. Now, at last, the ground is shifting. In February, Jill Sanborn of the FBI told Congress that “the greatest threat we face in the homeland today is that posed by lone actors radicalized online who look to attack soft targets with easily accessible weapons.”

Today, we can’t pretend that what happens online stays online. Its tendrils have crept into our everyday lives: A SWAT officer was pictured next to Vice President Mike Pence wearing a QAnon patch; a QAnon supporter won the Republican primary in Georgia. Female and minority politicians are assailed with the kind of language that would have been unthinkable 10 years ago.

Phillips told me that she dealt with the trauma of her rape and her immersion in sadistic trolling communities by dissociating. The British mental-health charity Mind describes dissociation as feeling “detached from your body or … as though the world around you is unreal.” That is, unfortunately, also a good description of being online, particularly the kind of online where the hours spent down a digital rabbit hole begin to seem more like real life than the three-dimensional world. The casual abuse of Twitter, the consumption of memes at the expense of their subjects and the “ironic” use of hate speech make the internet a giant machine for crushing empathy. We need to rebuild our connections with other people. “You have to think from the perspective of the butt of the joke,” said Milner.

The contrition of the champions of internet culture is part of a broader story of liberal disillusionment. Very few would claim, as Barack Obama did in his victory speech in 2008, echoing Martin Luther King, that “the arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice.” The anarchists, intellectuals, and geeks who thought taboos were for normies didn’t see the snake in the grass, because they thought that its poison was safely confined to history. It was a heady mix of privilege and naïveté, built on the promise of the internet as a space without repercussions.

“I was part of those circles,” said Phillips. “So this is not me pointing the finger at other people and saying they were bad. This is my own personal failing, in the context of lots of other structural, systemic failures … We didn’t have to think about consequences.”

Now, though, Phillips thinks about the consequences all the time. The consequences have ruined women’s lives. The consequences have terrified families at restaurants and worshippers in synagogues. The consequences are in the White House.

September 30, 2020 at 05:00PM

https://ift.tt/2Sc9wl7

How Memes, Lulz, and "Ironic" Bigotry Won the Internet - The Atlantic

https://ift.tt/2YfrSFy

/article-new/2021/06/iphone-13-duan-rui2.jpeg?lossy)

No comments:

Post a Comment